Here’s a change of pace, a bit of hidden surfing history.

“We are talking about the late 50’s and early 60’s, The Makaha Surfing Championships by Waikiki Surf Club was the premier international surfing event and there was no other major surfing event in Hawaii. They had body surfing, paddleboard races, tandem surfing, women’s surfing, junior men’s and senior men’s competitions. There were two-, three-, four thousand people on the beach and they’d decide in the morning, according to the surf, what event they would hold.”

Fred Hemmings, a champion surfer from way back, from an oral history by the Outrigger Canoe Club

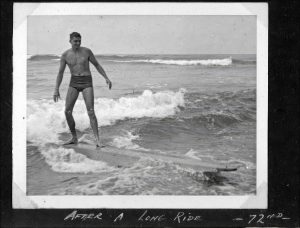

John Lind at Makaha, early 1960s.

The Makaha International Surfing Championships, as Hemmings recalls, was the original major international surfing contest in Hawaii.

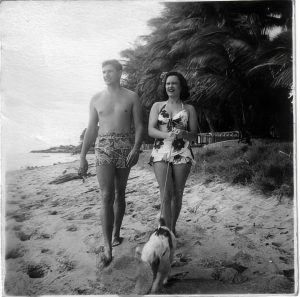

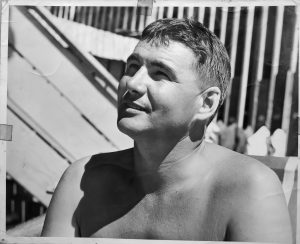

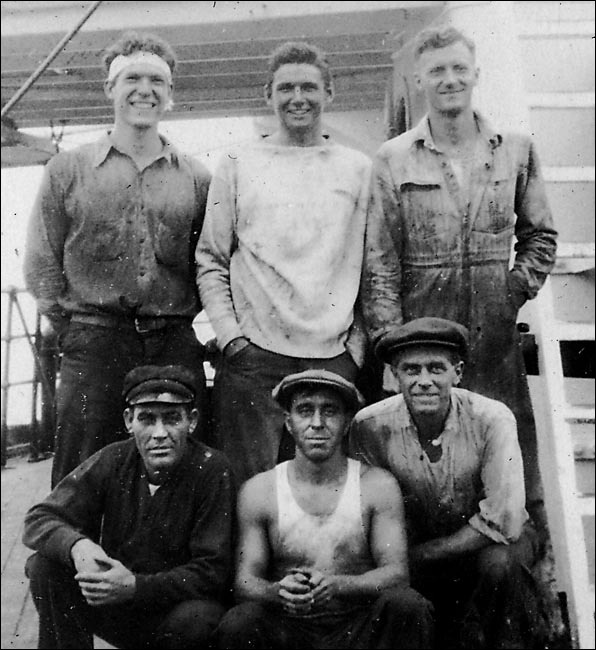

It was, by most accounts, originally the idea of my dad, John M. Lind, a transplant from Long Beach, California, who arrived in Honolulu as a young man in 1939. He had been one of those early California surfers. He loved the ocean, although he was never an outstanding surfer, but he excelled at organizing people and events. Before he came to Hawaii, he had been an organizer of what they dubbed “The First National Surfing Championship” held in Long Beach, Califoria, in 1938, working with other members of the Junior Chamber of Commerce.

He had been in Hawaii just four months when he became chairman of a group that announced formation of the Hawaii Surfing Association following a meeting at Honolulu’s city hall. Those attending the meeting were Walter Napoleon, Hiram Anahu, Tom Kiakona, Gene Smith, Art Powlison, Al Spohler, Jack May, N. Thomas, Brooks, and John Lind. The group quickly organized a day of surfboard paddling competition with a number of age groups, including categories for both men and women. The group later held paddling and surfing events through the years of WWII, with the last in 1944.

After the end of WWII, he became a co-founder and first president of the Waikiki Surf Club, and later approached the Waianae Lion’s Club with the idea of working together to put on an event at Makaha, with the first Makaha championships held in 1953.

In any case, a dispute between the Makaha event sponsors erupted as planning began for the 1958 contest.

This post tells the behind-the-scenes story. It originally appeared here on August 14, 2010.

The temperature in Honolulu rose to 86 degrees on August 19, 1958, but it probably seemed hotter as members of the International Surfing Championship Committee began arriving at the old Pearl City police station for their first planning meeting looking ahead to the next annual event at Makaha, considered the premier and most prestigious surfing contest in the world at the time.

Members of the committee represented the event’s co-sponsors, the Waikiki Surf Club and the Waianae Lions Club. The groups had worked together on the annual event for five years. In 1958, the committee’s chair was Waianae Lion’s president, William Jackman, who had come to Hawaii twenty years earlier and was stationed at Wheeler Army Airfield. He later became a senior civil service employee at Hickam Air Force Base.

Fireworks started as soon as Jackman called the meeting to order and announced the Lions had a proposal. He passed a copy of a written statement to Waikiki Surf Club president John Lind, then asked another Lion, David Klausmeyer, to read the prepared statement.

Klausmeyer announce the Lions had voted to withdraw as co-sponsors and instead take over and put on the event on their own.

The statement began by pleading inexperience and their own failure to follow rules established by the Internaional Association of Lions Clubs, which were described as “strongly opposed to any Lions Club co-sponsoring any project with another organization.”

But the Lions’ statement also cited “other pressures beyond our control,” which were not specified. One clue might be the reference to an interest in “fair unbiased competition”, possibly alluding to criticism already being heard from Austalian and California surfers who went home saying the local judges were biased in favor of Hawaiian surfers.

The Lions offered to turn the event back over to the surf club if, in the future, the Lions were unable to continue.

The Lions did not disclose that, prior to this meeting, they had already applied on their own for a permit from the city to use the Makaha Beach area for the event.

Lind, speaking on behalf of the Waikiki Surf Club, said he was shocked by the proposal and had no choice but to flatly reject it and, instead, accept the Lions’ decision to withdraw as co-sponsor, minutes of the meeting show.

After a brief private meeting, the WSC members announced their official decision to reject the proposal and instead “carry on the project alone.”

During an open discussion that followed, Klausmeyer claimed the idea of the Makaha championships had originated with the Lions Club. This was quickly challenged by WSC members, who said the idea was originally floated by Lind, who raised it during an invited presentation to the Waianae Lions about the organization of the Waikiki Surf Club.

Following the meeting, the WSC executive committee immediately moved to register the Makaha event name, negotiate the beach permit with the city, and assigning responsibilities for everything from security to food to judging, pushing ahead without their former co-sponsor.

On September 20, 1958, Lind wrote Jackman to confirm that the Lions were now out of the picture and to “arrange an early impeccable settlement with the Waianae Lions Club in connection with all the property relating to the project which we at present jointly own.”

Operating on a tight timeline, Lind said the program had been set for the weekends of November 22-23 and November 29-30.

Jackman responded with a request for a joint audit of the finances by the treasurers of the groups, and the audit was quickly set in motion.

What is most striking, from today’s perspective, is how little equipment and money was held after putting on the event for five years. There was $494.54 in the bank as of October 12, 1958, along with three umbrellas for judges, 20 event vests, 18 judges shirts and hats, and 13 souvenir shirts. Total current value of these items was estimated at $72.76.

The accounting also notes that Chinn Ho has not followed through with a donation promised in 1957, and had advised he would not contribute more than $250.

Ho had been a backer of the Makaha Championships from the beginning, apparently believing that the public attention and news coverage would increase the worth of his land holdings in the area.

The partnership between the two organizations officially came to an end on October 22, 1958, when a check for $247.27 was sent to the Lions Club from the championships account and another $82.12 from the Waikiki Surf Club “in full settlement of International Surfing Championships funds and property.”

Documents from these events

can be viewed in pdf format.

Footnote:

After writing this brief account of the 1958 incident, I decided to see whether my father, John Lind, had any recollection of the events. He was in a nursing home suffering from Alzheimer’s, and his memory, while fading, was unpredictable.

I don’t like to put him on the spot by directly asking whether he remembers something particular. In this case, I told him that I had been reading about the time in 1958 when the Lions Club attempted to take control of the Makaha event.

He immediately looked at me and said sharply: “Where did you read that?”

A short pause, then he continued: “I know it happened, but where was it published?”

Then he shook his head. “These are things no one talked about.”

He seemed to vaguely recall Jackman, but had a clearer recollection of Doak Klausmeyer. He said Klausmeyer, who appears as “David Klausmeyer” in the minutes of the meeting, lived in a house right next to the beach at Makaha. I’m assuming that Doak and David were the same person, although that could be wrong.

He relaxed after a minute or two, sinking into his pillow, and reflected: “I wonder what people will say about me when I’m gone?”

I left that question unanswered.

He died in October 2010, just a few months after this conversation about Makaha.

But it seems to me that “things no one talked about” are histories that need to be written.

So we crossed the street, myself and I, and sat on the seawall behind Swanzy Beach Park to watch the ocean at play. It was quiet, sunny, and clear. There were a few other people in the park, but I was alone with myself and the ocean. I thought about my father’s nearly 97 years, during most of which he swam, surfed, and fished in this same ocean. I let that connection wash over me, and willed it to wash over him as well, wherever he was or would be soon.